History

Charles Ives (1874-1954) was an American Composer born in Connecticut. He used the traditions of European classical music infused with the voice of the American people. Ives, like many great minds in their day, was not the most appreciated at first. He was patient and persistent, and eventually people started catching on. By the end of his life, he won the Pulitzer Prize for Music for his third symphony. Ives’ main profession was as an insurance executive and actuary, and he was incredibly rich from his work. A lot of his performances were paid for by himself or other benefactors. He was ahead of his time, and people adore and find excellence in his craft and his unique voice now. He was prone to sort of making a patchwork of different scales and harmonies. He especially loved piecing together popular American tunes and hymnal music found in the New England area. Ives wrote in all types of media, including vocal pieces. He published a book of songs in 1922 titled 114 Songs, which is comprised of pieces written between 1887 and 1921.

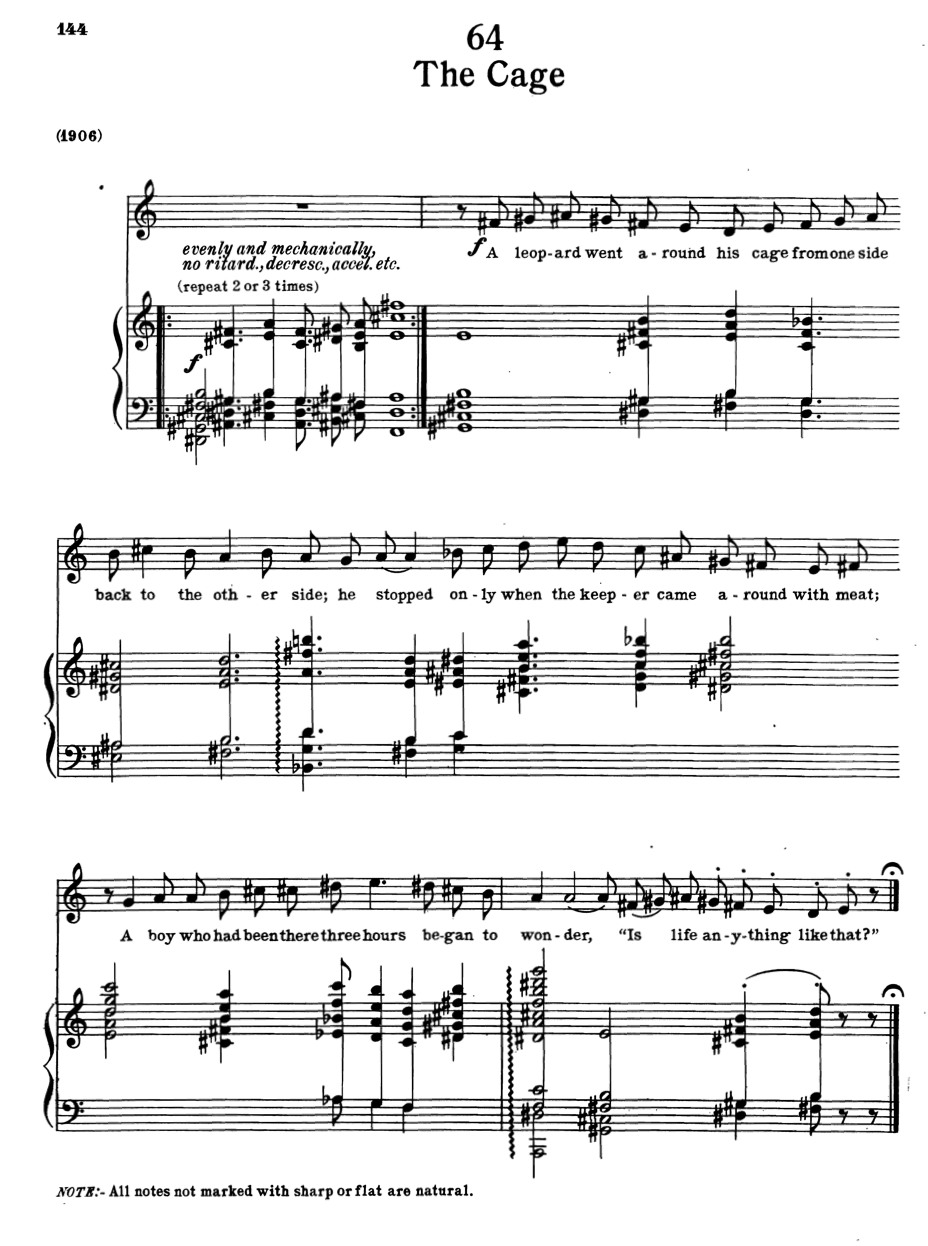

‘The Cage,’ from 114 Songs, shows Ives’ fondness for juxtaposing contrasting ideas. He isolates the whole tone scale in the vocal part and quartal harmony in the piano part. It showcases both harmonic palettes.

First let’s just listen to it….. thoughts? Weird? Totally out there? What was that? Ouch? Beautiful? I’ve never heard anything like that before? Does that make musical sense? Wait, maybe I liked it but I’m afraid to admit I may like something so “thorny.” Perhaps one or all of these thoughts just crossed your mind while listening to this piece.

Now let’s give it another listen. This time just listen to the singer. Can you hear what scale he/she is using? Ives is using the whole tone scale. There are basically two whole tone scales, one that starts on C ![]() and one that starts on C sharp

and one that starts on C sharp ![]() . As opposed to the Debussy piece which stayed in the scale that starts on C, Ives oscillates between the scales. Please note before looking at the score or notes that there is no key signature and only a couple of barlines, therefore all notes not marked with sharps or flats are natural.

. As opposed to the Debussy piece which stayed in the scale that starts on C, Ives oscillates between the scales. Please note before looking at the score or notes that there is no key signature and only a couple of barlines, therefore all notes not marked with sharps or flats are natural.

Something neat about the way Ives flips back and forth between the two whole tone scales, is the “thorny” result. It is impactful to have these scales displaced by a half step. If they were displaced by another interval, the spacial relationship would not be as close, and would not result in such a discordant way.

Let’s look at the scales and lyrics a little closer:

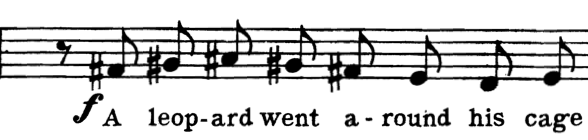

“A leopard went around his cage” those words belong to the scale that starts on C think of it like (C, D, E, F sharp, G sharp, A sharp etc)  . But as you can see “from one side back to the other side he stopped” – those words belong to the scale that starts on C-sharp.

. But as you can see “from one side back to the other side he stopped” – those words belong to the scale that starts on C-sharp. ![]() Ives then changes the scale again on “only when the keeper came around the meat,”

Ives then changes the scale again on “only when the keeper came around the meat,” ![]() and again on “a boy who had been there three hours began to wonder.”

and again on “a boy who had been there three hours began to wonder.” ![]() Can you see he breaks the pattern of the scale at the word “hours?” We return to the whole tone scale that starts on C for the last words of “is life anything like that”

Can you see he breaks the pattern of the scale at the word “hours?” We return to the whole tone scale that starts on C for the last words of “is life anything like that” ![]()

What about the words of this piece would cause Ives to keep going between these two scales?

Well, first of all there is the concept of a the cage. And what is there to do in a cage but pace back and forth? Which is what the leopard is doing. Ives is going back and forth between the two whole tone scales.

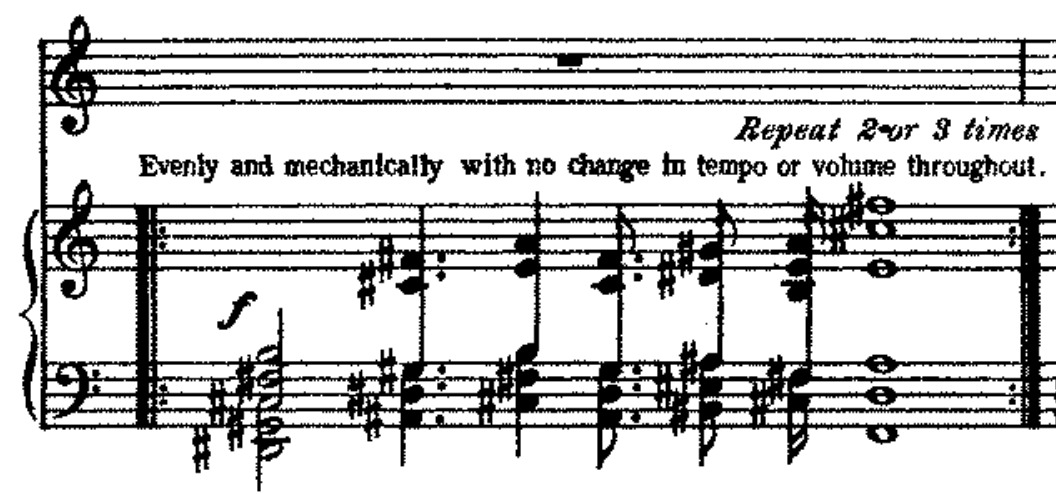

Another indication of text painting lies in the first measure in the piano. Text painting is emulating word meanings in the music, ex ascending scalar movement when describing climbing a ladder. Doesn’t the first measure look like a physical cage? There are bars going vertically down that are even more encompassed by the repeat sign and the double bars at each end of the measure. Ives is having (fun) with the meaning of this text.

Quartal Harmony

What’s happening under the melody in the piano? What is that harmony? What are those chords? What does that mean?

Well, after a while composers were getting tired of hearing the same tertian harmony, (harmony based on thirds) so they developed quartal and quintal harmony which is basically stacks of perfect 4th intervals or perfect 5th intervals instead of major or minor thirds.

As you can see in the first measure of ‘The Cage,’ the first chord is stacks of perfect fourth intervals (D sharp, G sharp, C sharp, F sharp, and B)

→

→

Same thing with the next note, the dotted quarter note (A sharp, D sharp, G sharp, C sharp, and F sharp)

and the next (C sharp, F sharp, B, E, A)

→

→

the next (A, D, G, C, F)

![]()

the next (B sharp, E sharp, A sharp, D sharp, G sharp)

→

→

the next (C sharp, F sharp, B, E, A)

![]()

and the last chord of that opening measure is a bit different, it is comprised a bit differently but in the middle of the chord we can see a quintal chord, built on stacks of perfect 5ths (D, A, E)

![]()

So All of this previous information comprises the “musical sense” of the piece – quartal and quintal harmonies moving under oscillating whole tone scales. Now that you know about these scales and harmonies and a little about the meaning of the text maybe you can listen with a new perspective? Give it a try! Why not? Don’t be like the leopard and be stuck in your cage. Life is not anything like that if you choose differently!

ASSIGNMENT

Go for it! Try and think in quartal or quintal harmonies. If this is beyond your scope, just practice writing out stacks of fourths or fifths. If this is a harmonic palette you’ve already worked in, perhaps you can do something Ivesian and patch together or juxtapose multiple scales and harmonies. Some of the scales we’ve learned are: whole tone, pentatonic and octatonic. Now we know quartal and quintal harmony.