History

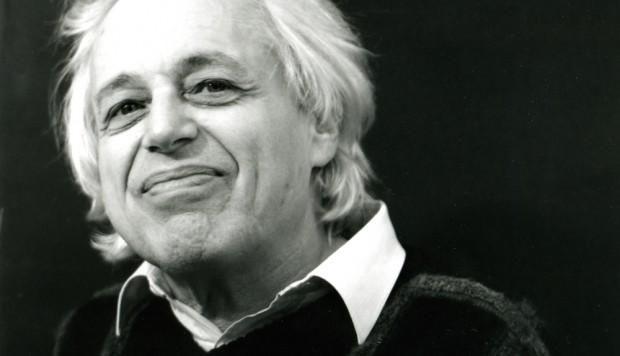

György Ligeti, (1923-2006) was a Hungarian composer. You may have heard his music in 2001: A Space Odyssey. Maybe you remember hearing some voices freaking out when the apes wake up to see the monolith (video). That is not an original score, but rather Ligeti’s Requiem (1963-65) for soprano, mezzo-soprano, two mixed choirs and orchestra. Like most composers, Ligeti went through different stages of style. Since Hungary was a communist state, there were certain restrictions placed on creativity. He emigrated to Austria in 1956, and found it much easier to work in an avant-garde style. Avant-garde refers to unconventional creativity – ideas outside of the box that are strange, new, or experimental. When Ligeti emigrated, he began exploring electronic music and wrote alongside Karlheinz Stockhausen and Gottfried Michael Koenig (some people you may have never heard of but were important electronic music composers.) Ligeti completed two electronic compositions; his short time in this medium influenced how he heard texture and created sounds. Avant-garde and electronic music forged a pathway to create micropolyphony – a term coined by Ligeti. Micropolyphony is a kind of polyphonic musical texture consisting of many lines of dense canons moving at different tempos or rhythms, thus resulting in tone clusters vertically. If you don’t understand that explanation, perhaps Alex Ross’s The Rest is Noise may help. “In the nineteen-sixties, György Ligeti developed a technique of assembling large masses of sound from multiple layers of minute contrapuntal activity, with many different instruments playing the same material at different speeds.” But the overall impact is a hail storm effect resulting in sound-mass vs individual parts.

Before emigrating, Ligeti’s musical language resembled that of Béla Bartók, another fellow Hungarian composer. Ligeti may not have felt this way, and probably saw his language as something much simpler and with a different purpose. However, when writing music with pitch centers, it is hard to not compare to others who might also do the same. A pitch center is a piece that hovers around a certain pitch, but may not necessarily reside in a key.

In 1953, Ligeti wrote a piano cycle called Musica ricercata. The set contains eleven pieces. The whole work is based on note restrictions. The first piece uses two notes, the second piece uses three notes, and so on until the 11th piece uses all 12 pitches of the chromatic scale. The first piece uses only the note A, ending with a D, at the very end of the piece. The second piece then uses three notes: E sharp, F sharp, and G. After Ligeti wrote this cycle, he arranged six of the movements of Musica ricercata for wind quintet with the new title of Six Bagatelles for Wind Quintet.

György Ligeti_6 Bagatelles for Wind Quintet_excerpts PDF

This is not the full score to this piece. 6 Bagatelles for Wind Quintet was written after 1923, and is not in the public domain. Therefore, I cannot provide the full score here. I created a PDF excerpt to help explain some of the details, but you may need to locate a copy at the library, or order one from the publisher if you dig the piece. Schott Music

György Ligeti: 6 Bagatelles for Wind Quintet

Analysis

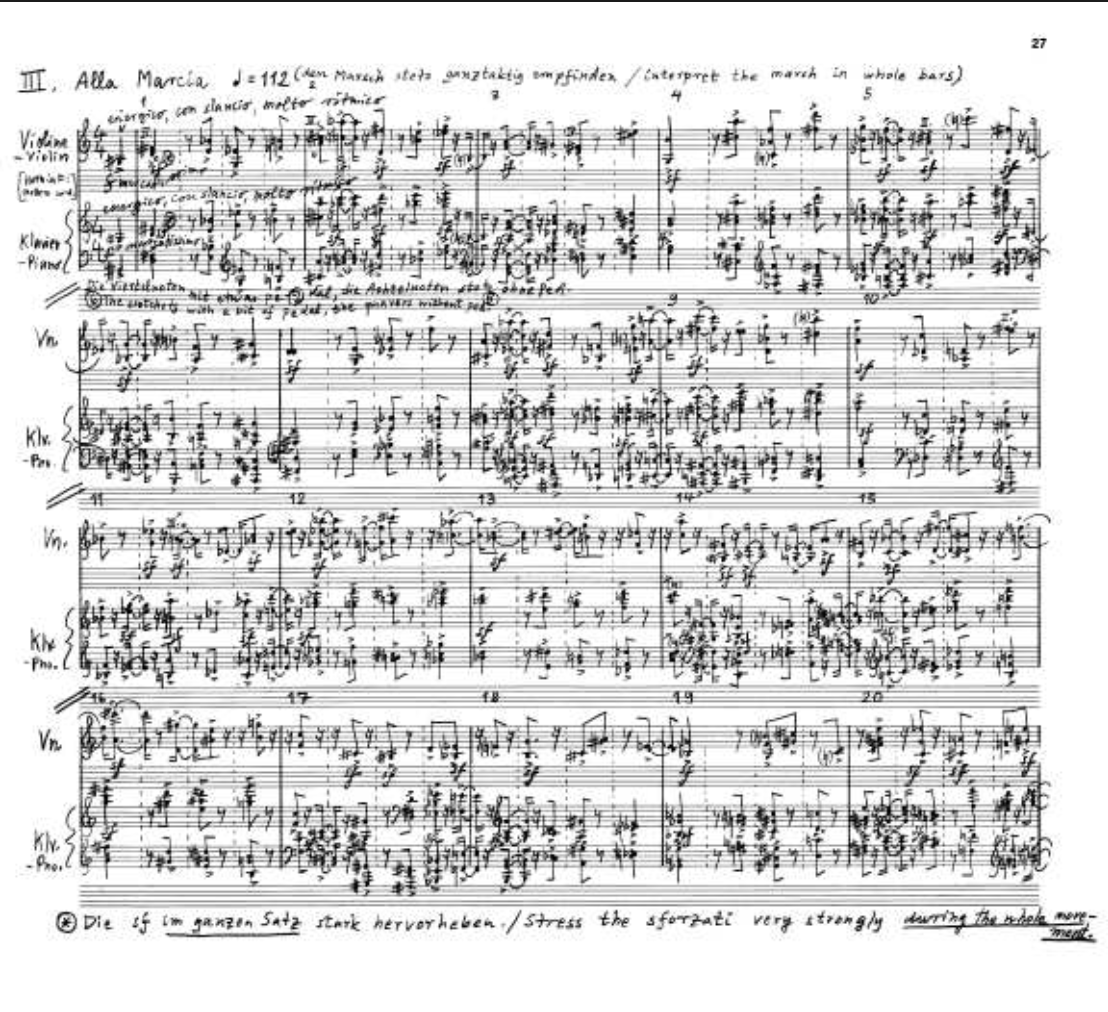

The first movement of the Six Bagatelles for Wind Quintet is an arrangement of the third movement of Musica ricercata. This piece demonstrates economy of material. Economy means? (Anyone? Bueller?) In this sense, it means intentionally restricting your musical material. You don’t need to come up with 80 new ideas to create a piece of music. You can work off of one idea; one idea can spawn a whole piece, a revolution, ruling the world! …Ok I’ll reign it in, but really it helps you to see what you can get out of one train of thought.

Let’s identify the pitch material in this movement. How many notes do you see? Remember that this is a transposed score, the clarinet and horn are both transposing instruments. There is a B-flat clarinet and a horn in F. So, the clarinet sounds a major second below where written. The horn sounds a perfect 5th below where written. For example, the first note in measure one of the clarinet is a written D, but a sounding C. ![]() → looks like a D but sounds like middle C.

→ looks like a D but sounds like middle C.

There are four notes in this whole movement: C, E flat, E, and G. You may be inclined to say this piece is in C major or C minor. But this piece isn’t exactly in a key, it’s more C centric. It revolves around C-major and C-minor triads. This may be confusing, but you can have a major or minor quality without necessarily being in a key. In movement I of 6 Bagatelles, there are no leading tones, no V chords or vii chords, no movement to anywhere really except C. In “tonal” music, part of establishing a key is to move away from the root chord to imply other harmony that makes up a specific key. In this case, Ligeti only wants to make a piece out of those four notes.

Let’s talk motives:

First of all, what is a motive? A motive is a small musical idea, or musical fragment. It generally reappears with purpose and is shorter than a full-blown melody. A melody, for example, may be constructed using motives.

With that in mind, look at the flute and the oboe in measure one. The motive here is two sixteenth notes followed by two eighth notes followed by two quarter notes. ![]() This motive starts on the second half of beat one with punctuated downbeats in the other instruments. So what’s special about that? Essentially, Ligeti took the idea of two sixteenth notes and augmented them – stretched them out. The rhythmic motive in itself is an augmentation of its initial device. Two sixteenths augmented to two eighths and then to two quarter notes. This shows the economy of his motivic use, not just in pitch material, but in rhythmic content as well.

This motive starts on the second half of beat one with punctuated downbeats in the other instruments. So what’s special about that? Essentially, Ligeti took the idea of two sixteenth notes and augmented them – stretched them out. The rhythmic motive in itself is an augmentation of its initial device. Two sixteenths augmented to two eighths and then to two quarter notes. This shows the economy of his motivic use, not just in pitch material, but in rhythmic content as well.

Now, let’s look at the phrasing. The first phrase is five measures long. It so happens that the second phrase is also five measures long. But what is the difference between them? Well, the first phrase hovers around a C-minor triad, whereas the second phrase arpeggiates through a C-major triad providing a shift in timbre. ![]() You may also notice the “Major” utterance of the motive starting on the second half of beat three as opposed to the first half of beat one. Another differences includes shifting in texture when the bassoon enters at measure six. There’s something about the bassoon part that looks familiar too. What could it be? What about this

You may also notice the “Major” utterance of the motive starting on the second half of beat three as opposed to the first half of beat one. Another differences includes shifting in texture when the bassoon enters at measure six. There’s something about the bassoon part that looks familiar too. What could it be? What about this ![]()

![]() has to do with any of the material we have discussed so far? The bassoon is grouped into five note arpeggios. Therefore, the number of measures per phrase is reflected in the number of notes per arpeggio. Now, let’s look at the third phrase beginning on measure eleven. Recap – the first phrase is C minor(ish) and the second phrase is C major(ish), but the third phrase is a combination of the two. The rhythmic motive utilizing the C-minor chord starts on the second half of beat one, and the rhythmic motive utilizing the C-Major chord stars on the second half of beat three. When that concludes, the music moves on – the horn and the bassoon pump out eighth notes in thirds, and the piccolo enters providing a new color. New texture is initiated by the addition of two previous phrase structures.

has to do with any of the material we have discussed so far? The bassoon is grouped into five note arpeggios. Therefore, the number of measures per phrase is reflected in the number of notes per arpeggio. Now, let’s look at the third phrase beginning on measure eleven. Recap – the first phrase is C minor(ish) and the second phrase is C major(ish), but the third phrase is a combination of the two. The rhythmic motive utilizing the C-minor chord starts on the second half of beat one, and the rhythmic motive utilizing the C-Major chord stars on the second half of beat three. When that concludes, the music moves on – the horn and the bassoon pump out eighth notes in thirds, and the piccolo enters providing a new color. New texture is initiated by the addition of two previous phrase structures.

This middle section provides the listener with a unique perception. But why? It’s the same four notes, and the same general rhythm. Measure sixteen sounds like there are different notes… why? It’s the same notes. Ligeti uses larger intervallic skips to widen the musical material. It contains the same set of notes, but larger intervals form new motivic intent. In this section, he places the minor seconds right next to each other.

It contains the same set of notes, but larger intervals form new motivic intent. In this section, he places the minor seconds right next to each other.

Assignment

Choose your own four notes. You may write for whatever ensemble floats your boat. Think about economy of material – purposefully restricting musical material. You may accomplish this through rhythmic and phrasic structure as well, just like Ligeti. Perhaps you may think of your own version of this, including personal style of variation. Ideas to consider are: motivic use, augmentation, diminution, overlapping elements, use of dynamics and articulation, etc. Have fun!